First up, what exactly is contextual support?

The term ‘contextual support’ itself lends the biggest hint, it’s being able to support your users proactively, where and when they are in most need of help.

con·tex·tu·al (kn-tksch-l, kn-)

adj.

Of, involving, or depending on a context.

Remember clippy, the office assistant in MS Office 97? That little dude everyone hated and became a cult classic due primarily to popping up at the most inappropriate of times.

Well, Clippy was the first experience of contextual support for hundreds of thousands of people, and it left a bad taste in their mouth from its poor execution. The general idea of clippy was to proactively provide tips and support for people when the system determined they were having trouble with a particular task (only he was a little too anxious).

But elevio, a new contextual support based startup is aiming to fix all this. I’ll get back to them later, but first…

What’s wrong with existing support systems?

Traditional support systems like Zendesk and Desk do a splendid job of providing systems to allow site owners to converse with their users when they run into troubles.

The trouble is, they are reactive systems. They rely on the user being patient enough to take the time to abandon what they were attempting and file a support ticket, and wait patiently for a reply which could (should) be super fast, but we’ve all been in the situation where we need to wait until the next morning or worse, Monday, for our support ticket to be replied to.

It’s been written about time and time again, that you more often than not only get one chance to win over a potential customer. If they don’t get your product, they’ll leave. If you’re relying on your customers taking the time to ask for your help, you’re doing it wrong.

Even directing the user to an FAQ or a knowledge-base isn’t going to smooth over rough seas with them. It’s like telling your user “yeah, we know our products hard to use, go over here and look around until you find the help you need”.

First of all, don’t make your user support themselves. Second, what if they don’t even know what to look for? They bail, that’s what.

Examples of contextual support services

Providers of contextual support are few and far between at the moment, as it’s still something that’s making its way back into the fore since the atrocity that was ‘clippy’, but the companies listed below cover the regrowth each with a different approach.

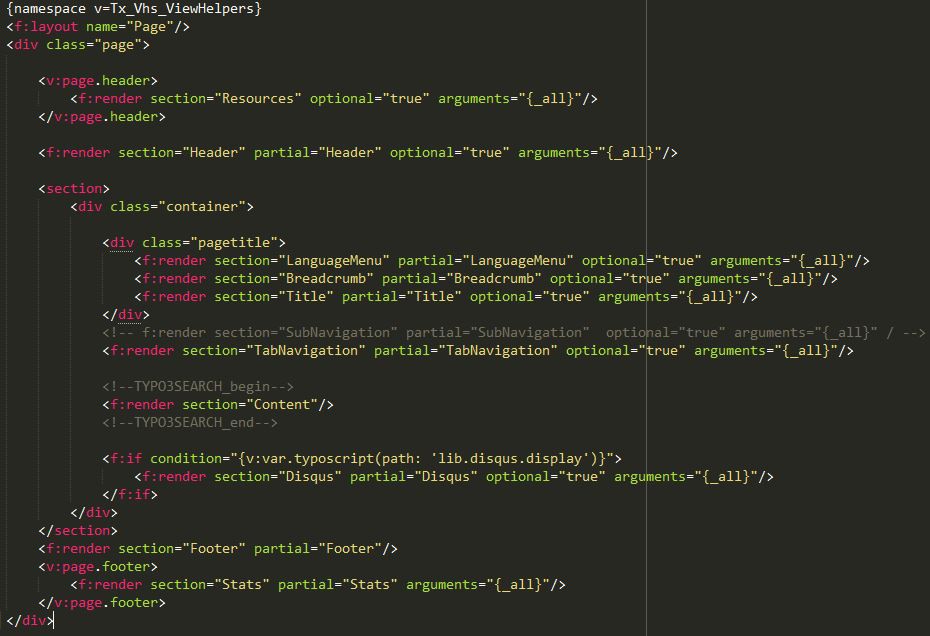

With each of the following services, they simply require a one off piece of code to be placed on your site or app, after that all content and messaging is managed via their own admin interfaces. Each charge a monthly fee.

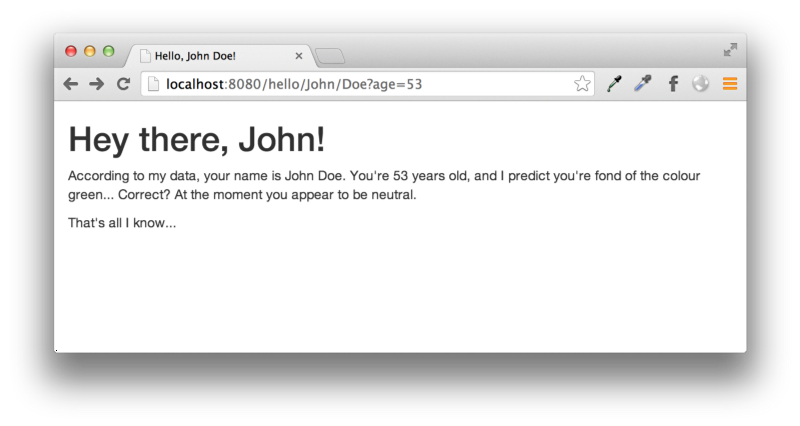

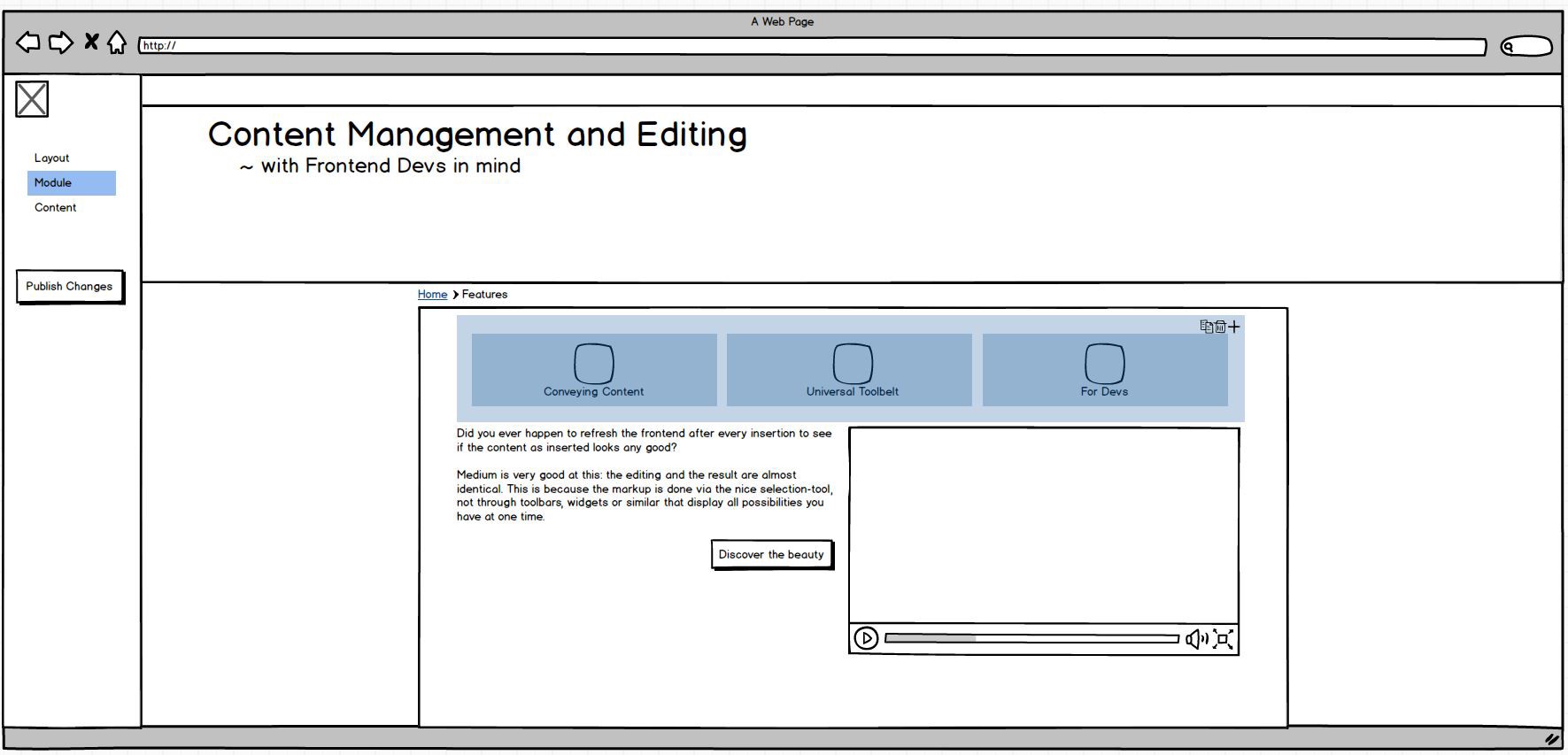

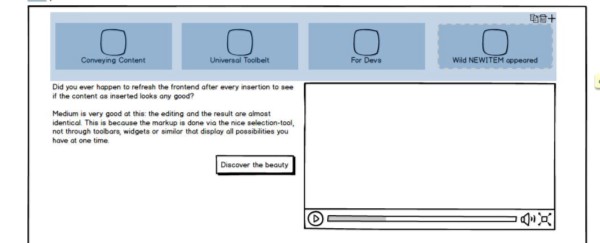

Elev.io

Elev.io is a new startup that provides contextual support to users of your site regardless of their status, they can be logged in users, or brand new general public users.

For example, a telephone company could create a tip with information including an image explaining where to find your account number on your latest bill, so when their customer is trying to login to their account using their account number, they can click on a little icon beside the input field, and the tip will be displayed for them.

They read the tip, close it, and fill in the form without losing focus or breaking stride. No external help was needed, no searching FAQs, no waiting for support staff to reply.

Over time, as collated user behaviour is monitored, insights can be seen on the admin panel letting you know where the pain points are for your users based on where they are opening tips most often, and which tips aren’t working based on user feedback. Using these insights, you know where you need to work in removing any road blocks.

Intercom.io

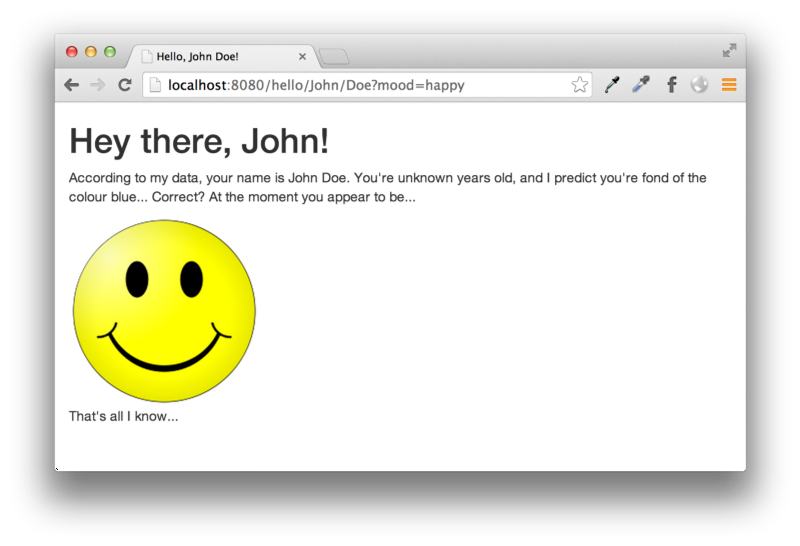

Intercom is a great service that allows site owners to provide proactive support, based on the data that you provide it on your users behaviour. You need to provide information on each user in order to be able to send them any type of message (alert, conversation or email), meaning this can’t be used with guests / public users, only logged in users of your site.

If a certain set of filters is met (that you define), an automated message can be sent to the user to either prompt them to complete some particular action, or ask them if they need a hand if they look stuck.

While it’s still somewhat reactive in it’s approach since it waits until the user has taken some action (or hasn’t taken action for a period days), it still leaves room for providing the answers a user needs, when they need them.

With the recent $23M Series B funding received by intercom.io, it’s evident that investors are prepared to bet that contextual support is an industry that’s here to stay.

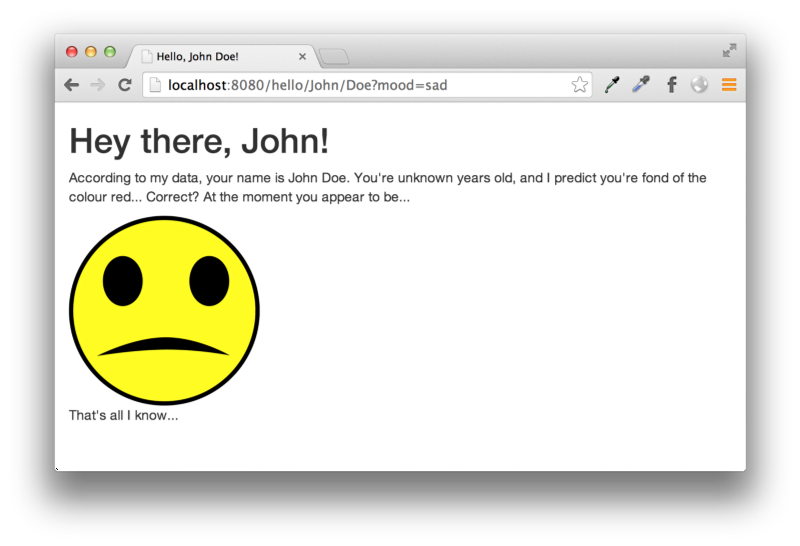

Mixpanel In-app Notifications

The in-app notifications tool by MixPanel is another service that allows you to send in app messages to users of iPhone apps, based on how you segment the data you’re receiving from their usage.

The example they provide in their video is to provide tips to people on how to beat a certain level in a game if the user looks like they are spending way too long on it.

The in-app notifications tie into mixpanels main platform, so you can view reports based on the effectiveness of your in-app messages. Did users ignore them, or did they follow your advice and move forward? Did users who followed your advice power forward, or stop after that little push?

Should I be using contextual support?

It’s not a completely black and white answer. In its simplest form, if your website is very self explanatory then there’s probably no need to hand-hold your users.

However if there’s the potential for people to get stuck on hurdles, particularly in the vulnerable on-boarding stages, then contextual support can be a godsend.

Contextual support is dead, long live contextual support.